Disorders of the Gallbladder and Bile Ducts

- related: GI

- tags: #GI

Asymptomatic Gallstones

Gallstones can be characterized as either cholesterol stones or pigment stones, which are black or brown. Cholesterol stones are the result of supersaturation of the bile with cholesterol; they account for approximately 75% of cases in the United States. Risk factors for cholesterol cholelithiasis include older age, female sex (twice as likely as in men), American Indian ethnicity, Western diet, pregnancy, rapid weight loss, obesity, total parenteral nutrition, and drugs such as estrogen and somatostatin analogues. Black pigment stones, usually composed of calcium bilirubinate, can form in patients with chronic hemolytic disease states, ineffective erythropoiesis, ileal disease such as Crohn disease, and cirrhosis. Brown pigment stones are composed of unconjugated bilirubin and varying amounts of other substances, such as cholesterol, but also contain bacteria. These are typically found in patients with biliary stasis and bacterial biliary infection, as can be seen in chronic biliary obstruction.

Gallstones are commonly discovered when patients undergo abdominal imaging for unrelated reasons. Ultrasound and CT can identify gallstones, whereas plain radiography identifies gallstones uncommonly.

Gallstones that are found incidentally do not typically cause any symptoms, and cholecystectomy is generally not recommended because most stones remain asymptomatic. Cholecystectomy is indicated in asymptomatic patients at high risk for gallbladder cancer, including patients with gallstones larger than 3 cm in size, porcelain gallbladder (intramural calcification of the gallbladder wall), gallbladder adenomas or polyps larger than 1 cm in size, or anomaly of pancreatic ductal drainage.

Biliary Colic

Biliary colic pain results from stimulation of the gallbladder in the presence of an obstructive cystic duct from gallstones or sludge. This pain is typically of relatively acute onset, is fairly severe and steady, and is located in the right upper quadrant or epigastrium. Pain may radiate to the right scapula and can be associated with nausea, vomiting, and diaphoresis, lasting 2 to 6 hours. This symptom complex may be precipitated by eating a fatty meal, which causes gallbladder contraction. Patients with unrelenting right-upper-quadrant or epigastric pain generally do not have biliary colic.

Patients with typical biliary colic symptoms and gallstones on imaging should undergo cholecystectomy, as the risk for complications from gallstones is approximately 2% to 3% per year. Complications include choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis. Patients with atypical symptoms should be evaluated for other causes.

Acute Cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis develops in the setting of cystic-duct obstruction and gallbladder inflammation. In many patients, infection of the gallbladder ensues. Patients typically present with severe right-upper-quadrant or epigastric pain lasting longer than 6 hours, accompanied by fever and localized peritoneal signs in the right upper quadrant. A positive Murphy sign (arrested inspiration upon contact of the gallbladder wall with the examiner's fingers) may be seen on physical examination. Laboratory studies may show leukocytosis; liver chemistries are not usually elevated in uncomplicated acute cholecystitis. The diagnosis can be made by ultrasonography showing gallbladder wall thickening and/or edema and a sonographic Murphy sign. A hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan (HIDA) can be used when the diagnosis is unclear, such as when symptoms suggest cholecystitis but the sonogram is normal.

Treatment includes pain control, intravenous antibiotics with gram-negative and anaerobic coverage (monotherapy with a β-lactam or β-lactamase, or combination therapy with a third-generation cephalosporin plus metronidazole), and cholecystectomy. Timing of cholecystectomy depends on the patient's surgical risk and response to antibiotics. An emergency operation is necessary in cases of suspected gallbladder perforation or emphysematous cholecystitis (infection of the gallbladder wall with gas-forming organisms such as Clostridium perfringens). For patients with low surgical risk, cholecystectomy, preferably laparoscopic, should be performed during the initial hospitalization. Patients who are deemed high-risk for surgery and who respond to antibiotics can be reassessed at a later time to determine if their surgical risk has decreased. In patients who are not good candidates for cholecystectomy and do not respond to antibiotics, percutaneous cholecystostomy tube or endoscopic drainage can be pursued.

Acalculous Cholecystitis

Acalculous cholecystitis typically occurs in critically ill patients and is a result of gallbladder ischemia that can be complicated by enteric bacterial infection. Risk factors for this condition include cardiac and aortic surgery, sepsis, burns, and vasculitis. The presentation depends on whether the patient is alert or sedated and mechanically ventilated. In alert patients, the presentation is pain, as seen in cholecystitis related to gallstones. In sedated or mechanically ventilated patients, it may present with leukocytosis, jaundice, and sepsis. The diagnosis is made using ultrasonography, which may show gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, gallbladder distention, or gallbladder-wall pneumatosis in the absence of calculi. In this setting, the gallbladder may not be visualized on a hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan.

Treatment consists of empiric intravenous antibiotics to cover enteric bacteria and cholecystectomy. A cholecystostomy tube may be needed if the patient is unstable or a poor candidate for surgery. The role of endoscopic gallbladder drainage is evolving. The mortality rate for untreated acalculous cholecystitis is as high as 75%.

Functional Gallbladder Disorder

The Rome 4 criteria for gallbladder disorders suggest that evaluation for functional gallbladder disorder is appropriate in patients with typical biliary pain in the absence of gallstones or structural pathology. Typical biliary pain is located in the epigastrium and/or right upper quadrant; is intermittent; lasts ≥30 minutes; crescendos and then plateaus; is severe enough to interrupt normal activities or results in an emergency department visit; and is not relieved by bowel movements, positional changes, or acid suppression. Supportive features include a gallbladder ejection fraction of less than 40% measured by cholecystokinin-stimulated cholescintigraphy and normal liver chemistry tests and pancreatic enzymes. Other causes of upper abdominal discomfort, including functional dyspepsia, peptic ulcer disease, and angina, should be carefully considered. Gallstones should be excluded by transabdominal ultrasonography. Endoscopic ultrasonography may be helpful if the transabdominal ultrasound is normal. If no other cause of pain is found and the gallbladder ejection fraction is less than 40%, cholecystectomy can be considered. The data supporting cholecystokinin-stimulated cholescintigraphy is poor. In clinical practice, it is not uncommon to see patients who have met these criteria and undergo cholecystectomy, but continue to have the same upper-abdominal symptoms postoperatively.

Common Bile Duct Stones and Cholangitis

Stones in the common bile duct are a leading cause of obstructive jaundice. Complications in patients with common bile duct stones are more common than in those with gallstones, but 20% of patients spontaneously pass the stones, and less than 50% of patients develop symptoms. Symptomatic common bile duct stones present with jaundice, abdominal pain, or pruritus due to obstruction of bile flow. Common duct stones may be visualized by transabdominal ultrasonography. In the absence of direct visualization, the combination of an elevated bilirubin level and dilated common duct (> 6mm) on ultrasonography makes the diagnosis of common duct stone highly likely. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the preferred therapeutic method for stone extraction and should be performed in patients with a high likelihood of choledocholithiasis. In patients who are suspected of having common bile duct stones but have indeterminate findings on ultrasonography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic ultrasonography should be performed to avoid the risks of ERCP. Cholecystectomy should be performed within 2 weeks of stone extraction. Intraoperative cholangiography and ultrasonography are other alternatives for assessing for the presence of common bile duct stones.

The presence of cholangitis is heralded by the onset of the Charcot triad (fever, jaundice, and right-upper-quadrant abdominal pain) or Reynold pentad (Charcot triad plus hypotension and altered mental status). Cholangitis is potentially life-threatening, and antibiotic therapy targeting gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae should be administered. Identified common bile duct stones should be removed urgently with ERCP in patients with cholangitis, after which elective cholecystectomy should be performed during the initial hospitalization or within 2 weeks to reduce the risk for complications. In patients who are not surgical candidates, endoscopic sphincterotomy can be performed to facilitate the passage of additional common bile duct stones.

Gallbladder Polyps

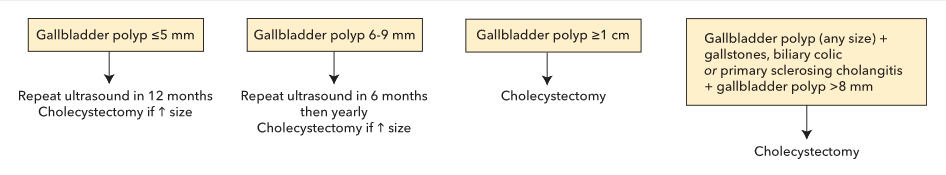

Gallbladder polyps, usually incidental findings, can be seen on 1% to 5% of gallbladder ultrasounds. They can be neoplastic, such as an adenoma, or nonneoplastic, such as cholesterol polyps or adenomyomas. The best predictor of a malignant or premalignant lesion is size of the gallbladder polyp, with polyps greater than 1 cm in size being more likely to be neoplastic. Gallbladder polyps associated with gallbladder stones or primary sclerosing cholangitis are also more likely to be neoplastic. Management of gallbladder polyps is outlined in Figure 32.

Gallbladder Cancer

Gallbladder cancer is the most common biliary cancer in the United States, but it is rare, with 3700 new cases per year. Risk factors include female sex, ethnicity or race (American Indian, Alaskan native, Black), cholelithiasis, gallbladder polyps, porcelain gallbladder, anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction, and obesity. The gallbladder serves as a reservoir for Salmonella typhi in chronically infected patients, and patients with this organism are at higher risk for gallbladder cancer.

Presenting symptoms may include right-upper-quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, or jaundice in advanced cancers, and biliary colic in early cancers. Gallbladder cancer should be suspected if an enhancing gallbladder mass is seen on CT or MRI.

Early gallbladder cancer is most commonly diagnosed incidentally at the time of cholecystectomy performed for biliary colic. Incidental tumors found to invade the lamina propria (stage T1a) do not require further treatment, whereas more advanced lesions require extended cholecystectomy.

The treatment of choice for gallbladder cancer is surgery. Treatment for unresectable disease can include chemotherapy with or without radiation, or palliative care.

Prophylactic cholecystectomy is recommended for patients with an anomalous pancreaticobiliary junction, gallbladder polyps 1 cm in size or larger, or gallbladder polyp(s) in the presence of biliary colic or gallstones; it is also recommended for patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and a gallbladder polyp larger than 8 mm in size. Prophylactic cholecystectomy can be considered for porcelain gallbladder or for gallstones larger than 3 cm in size.

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma, although rare, is an increasingly recognized malignancy. It is classified as (1) intrahepatic—seen in the smaller bile ducts entirely within the liver parenchyma; (2) hilar—most commonly arising from confluence of right and left hepatic ducts (Klatskin tumor); or (3) distal—arising distal to the cystic-duct entrance. Risk factors include primary sclerosing cholangitis, choledochal cysts, liver flukes (Opisthorchis), exposure to thorium dioxide (contrast medium), and hepatolithiasis. Symptoms vary with tumor location and may include jaundice, pain in the right upper quadrant, and constitutional symptoms.

Intrahepatic, hilar, and distal cholangiocarcinomas can occur in patients without liver disease. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma can complicate cirrhosis, and hilar cholangiocarcinoma can complicate primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Diagnosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma requires imaging with CT or MRI, and usually a biopsy. An elevated CA 19-9 level is supportive but insufficient for diagnosis. First-line therapy for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma is resection. Locoregional and/or systemic chemotherapy are appropriate for patients who are not candidates for resection.

Diagnosis of hilar cholangiocarcinoma can be challenging and is made by a combination of MRCP and ERCP. During ERCP, bile-duct brushings should be obtained for cytologic examination and fluorescence in situ hybridization testing. The latter test uses DNA probes to evaluate for gain or loss of chromosomes or loci, which are often present in biliary cancer. An elevated CA 19-9 level is supportive, but repeat ERCP is often required every 2 to 3 months to make the diagnosis. First-line therapy for hilar cholangiocarcinoma is resection. Patients with obstructive jaundice may require ERCP with stent placement to allow for biliary drainage. Patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma smaller than 3 cm in size and without extrahepatic spread can be evaluated for liver transplantation at select centers with neoadjuvant chemoradiation protocols. However, percutaneous or transluminal biopsy of hilar cholangiocarcinoma excludes a patient for liver transplantation due to the risk for tumor seeding.

The preferred treatment for distal cholangiocarcinoma is a Whipple resection.

Metastatic cholangiocarcinoma of any variety should be treated with gemcitabine-cisplatin.

The 5-year survival rate for patients with cholangiocarcinoma (excluding liver transplant recipients), including those who undergo resection, is 20% to 30%.